By ROBERT MEYEROWITZ

Bank spending in well-worn groove

Billions of dollars flow through South Carolina every year, to contractors and others, for roads and other infrastructure projects. The money comes from three pots, essentially: funds sent from the General Assembly through the state Department of Transportation; federal dollars channeled through SCDOT; and money, usually borrowed, spent by the state Transportation Infrastructure Bank, or STIB.

The STIB accounts for the largest component of the state’s bond debt, with $2.4 billion in liabilities. Debt service alone on its revenue bonds in fiscal year 2015 was about $156 million.

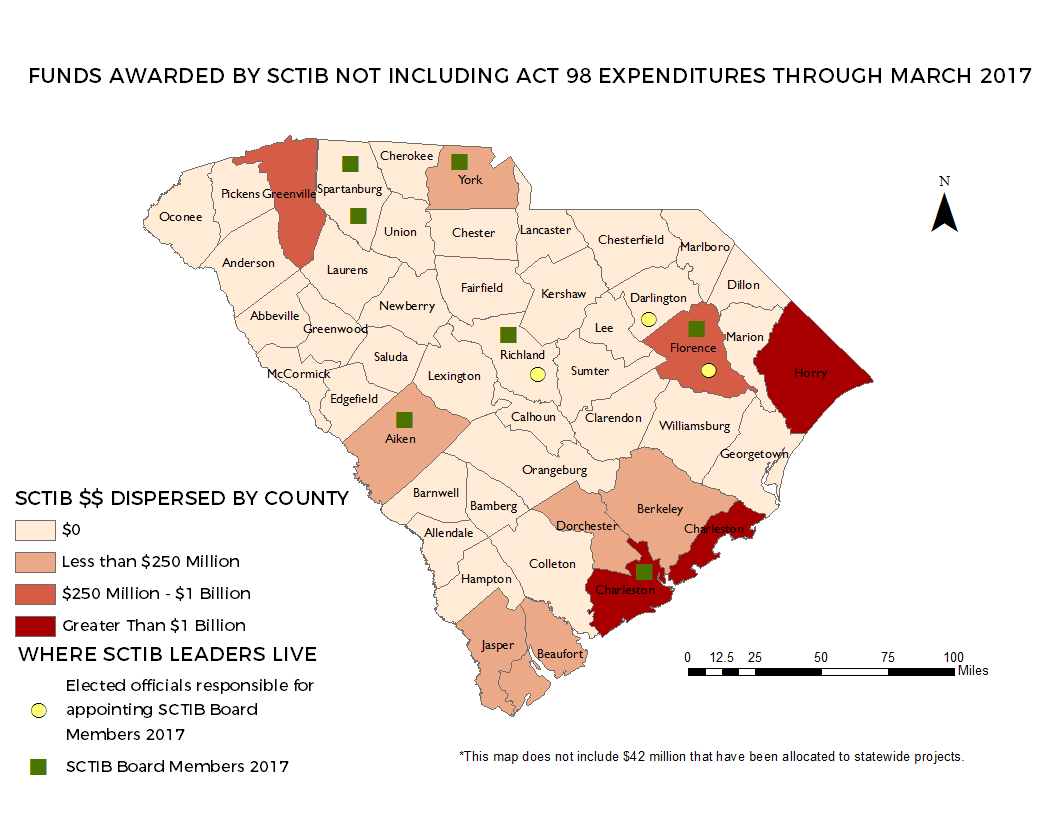

That borrowed money is primarily spent to build new roads and expanding existing ones. A new map (below, click to expand), created using data compiled by the Legislative Audit Council and updated by the Coastal Conservation League, shows how it flows.

An older version of this map, from 2012, showed much the same thing. Notable is that the trend continues. From the bank’s inception in 1997 until 2012, it had spent about $4.2 billion. Since then, it’s spent approximately another $600 million in the same way, funneling it more often than not to big projects in the home areas of its board members and of the legislators who appoint them, and no money at all to most counties.

Some of that may change after the General Assembly in the last session altered the kinds of projects STIB may finance. Formerly, those projects had to have a price tag of at least $100 million, from combined local funds and STIB matching monies. That’s been lowered to $25 million, which in theory could lead to more varied and geographically-distributed efforts, although the effects aren’t seen yet.

The map also does not include funding via Act 98, passed by the General Assembly in 2o13, by which $50 million a year is moved from SCDOT to the STIB to let it borrow by bonding to finance such things as replacing bridges and widening interstates. The STIB board has less discretion about spending that money.

Vince Graham, the Charleston developer who was appointed by Gov. Nikki Haley to chair the STIB board in late 2014, then replaced by Gov. Henry McMaster about a month ago, recently looked at the new map and said, “I thought there would be more counties.”

Still, Graham said, what’s seen in both maps is a similar story: From the bank’s founding in 1997, there was a concentration of big projects. “Something like 60 percent of all the funding took place on the first six or seven,” he explained, about $3 billion worth.

Since the inception of STIB, “funding commitments by the agency have been focused in Horry and Charleston counties,” the Legislative Audit Council found last year. The bank currently has the capacity to bond for about another $770 million in transportation funding, of which $420 million has been set aside as the state’s match for the proposed I-526 extension in Charleston, across Johns and James islands.

Nerve stories are always free to reprint and repost. We only ask that you credit The Nerve.