With this commission, there will always be problems

By HANNAH HILL

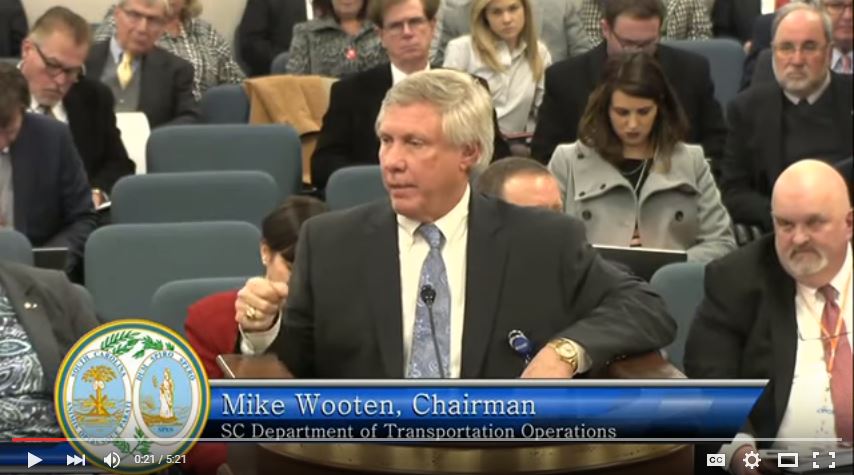

When Mike Wooten resigned from the state Department of Transportation commission, he blamed the ethics provisions in the gas tax hike bill just passed by the General Assembly, saying “The new law basically states that commissioners cannot apply for permits from SCDOT, so, if I stayed on the commission, I would have to abandon my business and I am certainly not willing to do that.”

This is significant for two reasons.

First, he’s basically admitting to having had conflicts of interest. Just to be clear, obtaining DOT permits for his business isn’t all he’s done:

- His firm, DDC Engineering, has received small payments from the State Transportation Infrastructure Bank (STIB) although he couldn’t remember what for when The Nerve asked him about it in 2015.

- He used his influence as a commissioner to make sure the Coast Regional Transit Authority paid its subcontractors, which included DDC Engineering. In an email, Wooten said “From my perspective, if (Coast RTA isn’t) willing to take responsibility, there shouldn’t be any ‘slack’ cut for them on the SCDOT side. You won’t hear a peep out of me if you take a hard line.”

- DDC Engineering has had millions of dollars in contracts and subcontracts with the same local government agencies who receive funding from and rely on good relationships with the DOT.

However, he is correct that the law has gotten much more specific regarding what commissioners may or may not do:

The commission or a member thereof may not enter into the day-to-day operations of the department, except in an oversight role with the Secretary of Transportation, and is specifically prohibited from taking part in:

(1) the awarding of contracts;

(2) the selection of a consultant or contractor or the prequalification of any individual consultant or contractor;

(3) the selection of a route for a specific project;

(4) the specific location of a transportation facility;

(5) the acquisition of rights of way or other properties necessary for a specific project or program; and

(6) the granting, denial, suspension, or revocation of any permit issued by the department.

A member of the commission may not have any interest, direct or indirect, in any contract, franchise, privilege, or other benefit granted or awarded by the department during the member’s term of appointment and for one year after the termination of the appointment.

This brings us to the deeper issue here: Will the new law be enough to protect the people of South Carolina from self-interested commissioners?

No – and here’s why:

Governor McMaster has already appointed Wooten’s replacement: Tony Cox, the executive vice president of a major real estate company in Myrtle Beach. Cox may well be an excellent choice as far as personal qualifications go, but it’s no secret that real estate developers have just as much at stake in infrastructure decisions as road construction companies.

Which raises an unavoidable question: Is there any other kind of commissioner candidate?

The obvious – some would say the only – choices for DOT commissioners are the guys on the ground with a thorough understanding of both their communities and the infrastructure system. In other words, private sector industry leaders. It makes sense to appoint them – but the very thing that qualifies them most for the positions also creates an unavoidable set of competing incentives.

It is very difficult to disentangle the interests of the taxpayers and their own business interests. The new law Wooten referenced patched a few loopholes, but did nothing to address the underlying conflicts. It couldn’t, because they are inherent in the DOT commission structure.

The only way to eliminate them is for those in charge of infrastructure to answer directly to the people, with no personal business interests in between. Ostensibly, you could choose engineers and planners from the academic or bureaucratic sectors, but at least some of these people are already employed by the DOT.

Which brings us to the only real solution: eliminate the commission entirely and allow the experts to do their job, accountable directly to the people of South Carolina through the governor.

You saw that one coming, didn’t you?