South Carolina’s murky world of tomorrow

By ROBERT MEYEROWITZ

South Carolina, like every other state, is in the business of building roads. It’s a big business: Four of the top 10 vendors for the state in 2016 were roads contractors, accounting for $175 million in spending alone. And that doesn’t reckon the opportunity cost — all of the things that don’t get funded because roads do; I may say conservation, you may say law enforcement, but either way, there’s a magnified cost.

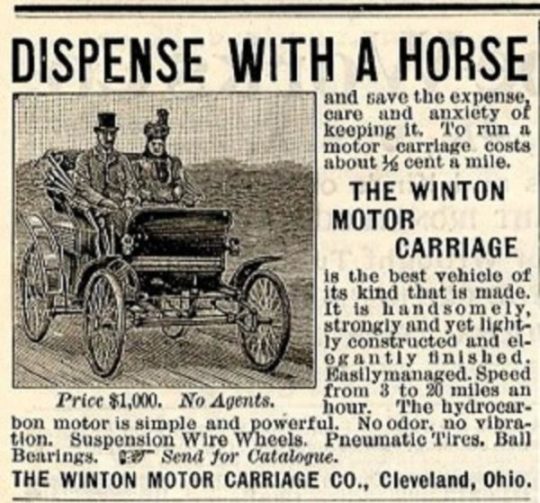

With that much treasure on the line, planning is critical, perhaps now more than at any time since the first Model T Ford was built, in 1908.

A recent post on Of Two Minds, the blog of the urbanist and finance writer Charles Hugh Smith, addresses what he calls “The False Promise of Infrastructure Spending,” something that ought to be of as much concern to Americans anticipating what President Trump has touted as the biggest infrastructure stimulus in our history as for South Carolinians who expect to see the state Department of Transportation spend money from the recent gas-tax increase on road work.

Many Americans seem to want a massive new federal investment to fix our “crumbling infrastructure,” perhaps because this is one of the few areas, besides reviling the Trans Pacific Partnership agreement, where Trump and Hillary Clinton agreed in the late campaign. Never mind that, as one sound analyst puts it, Trump’s infrastructure plan “is almost certain to be an epic disaster of bad incentives.”

Looking to the future, Smith has some similar reservations:

A rigorous cost-benefit analysis might conclude that some aging, marginal infrastructure should be torn down rather than replaced. If self-driving vehicles will reduce vehicles on the roads significantly — and some estimates range as high as an 80 percent reduction in traffic — perhaps we should wait for this technology to mature before spending trillions of dollars on infrastructure that is about to be under-utilized.

This is how a recent Forbes blogger, a finance researcher, framed the discussion:

Given the advanced state of driverless technologies and the amount of money being poured into the sector, there is little question — make that, no question at all — that within 10 years, driverless cars will be the norm…

There are currently about 1.4 billion cars on the road. Many of those cars, and eventually all, are going to be replaced by self-driving vehicles.

Car sharing is already growing in popularity. When getting a ride someplace is as easy and inexpensive as ordering an automated Uber, we can expect a significant percentage of people to realize car ownership is a thing of the past.

With proper maintenance, another significant expense, a road built tomorrow could be expected to have a life of 30 to 40 years. So highly expensive road construction now really ought to be looking to our anticipated needs in 2037 and beyond, which would mean at least considering whether we could need fewer roads.

The DOT, however, is planning among other things to widen roads, especially interstates.

Consider, too, that at the height of debate about the recent gas tax increase, DOT Secretary Christy Hall said that 54 percent of the roads in the state inventory are in such awful condition that they must be ripped up and rebuilt — at a cost of $8 billion. That’s a tremendous investment in an unchanging world.

This seems like something that at least ought to be on DOT’s radar, but over the course of several days, going through its communications department, we were unable to speak with or locate anyone who could tell us whether it even had considered the advent of driverless vehicles or how many cars might be on South Carolina roads in 2027, or 2037.

The South Carolina Alliance to Fix Our Roads, a group that represents the interests of roads contractors among others and lobbied for the gas-tax increase, doesn’t anticipate any big changes in road-building, says its president, Bill Ross. “I haven’t really heard any discussion, particularly in a state like South Carolina where we’re so married to our vehicles… none of the meetings I’ve been involved with and none of the national groups have been putting anything out on that.”

Some of the state’s roads inventory are rural and are said to be in need of particular attention. Driverless technology aside, not everyone is convinced that building new rural blacktop is the answer, either, especially if cost is a consideration — and when is it not?

A recent report from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program found that

… the practice of converting paved roads to unpaved is relatively widespread; recent road conversion projects were identified in 27 states. These are primarily rural, low-volume roads that were paved when asphalt and construction prices were low. Those asphalt roads have now aged well beyond their design service life, are rapidly deteriorating, and are both difficult and expensive to maintain. Instead, many local road agencies are converting these deteriorated paved roads to unpaved as a more sustainable solution.

For South Carolina, that would indeed be back to the future.