Comparisons raise questions about how well they’re working for whom

By ROBERT MEYEROWITZ

When it comes to higher ed, powerhouse four-year schools like USC and Clemson understandably get most of the attention in South Carolina and beyond — and much of it is positive, interspersed with concerns about mounting costs.

At the same time, in a state where education generally lags and there’s concern about a suitably educated labor pool, there’s probably more that ought to be said about its technical colleges. With university tuition continuing to rise even as wages remain flat, they offer an affordable, accessible alternative.

“During the 2016 to 2017 academic year, tuition and fees for full-time, in-state enrollment at a public two-year college averaged $1,760 per semester versus $4,825 at a public four-year institution and $16,740 at a four-year private school,” according to one recent study of nationwide trends in education. “Based on those rates, students who earn their general-education credits at a community college before transferring to an in-state public four-year university would save $12,260 over two years on tuition and fees alone.”

Yet there doesn’t seem to be much more to say that’s favorable about South Carolina’s technical colleges, the same study finds — even though they compose the largest higher education sector in the state, teaching more undergraduates than all other public colleges and universities combined, according to the South Carolina Technical College System.

So, we wondered, are the technical colleges, which are funded by tuition, state appropriations, and lottery contributions, still doing their jobs?

They have their origins in a long-ago initiative by Fritz Hollings. “I was at a Lutheran conference in Dayton, Ohio,” Hollings recalled, “and as we came out, it was almost 11 o’clock at night, I happened to look over and said, ‘What kind of industry is that working all night long? Let’s go over and look at it.'”

This was in 1958, when Hollings was South Carolina’s lieutenant governor.

“Well,” Hollings continued, “it was a technical training college. And I said, ‘I’ll be damned, the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer! We don’t have anything like that in South Carolina.’ I was running for governor at the time, and I said, ‘If I ever get the chance, that’s the first thing I’m gonna do.'”

And he did

The creation of the technical colleges — South Carolina’s community college system — was intended to stem the migration of African-American and other poor laborers, who left in search of work for places such as Ohio and Michigan. It was meant to turn farmhands into factory hands through training.

Two-thirds of the workforce then was functionally illiterate, one survey showed. Fewer than 5 percent of high school graduates went to college.

Some powerful state legislators, such as state Senator Edgar Brown, who chaired the Finance Committee for 30 years, resisted the idea of funding education for what he called “dummies.” Textile manufacturers, who dominated the economy, were also hostile to the state training workers, Hollings recalled, because they were suspicious they’d have to pay higher wages to keep them.

Hollings and others persisted, and established the Special Schools program, the forerunner of today’s Ready SC. It came in handy.

“Even before we could get the colleges up and going, before we could turn out graduates with these skills, we could go out and tell businesses in the Northeast, ‘If you’ll bring a manufacturing plant to South Carolina, we will study your processes, we will develop a training program, and Day One, when you’re ready to flip that light switch on and get your assembly line going, we will have people trained for you — and that won’t cost you a dime,” recalled Barry Russell, former president of the Technical College System. “That was new then, and it worked.”

The colleges began with the Greenville Tech school in 1962. By the end of the ’60s, there were 12 schools around the state.

In 1972, after USC resisted a plan to make them part of a community college system, because USC feared its political clout would be diluted, they became the technical college system. “Technical” was assumed to have more appeal to prospective employers than “community,” although many parents associated it, negatively, with “vocational.”

In the 1980s, the technical colleges emphasized high-tech training, including computers and robotics. In 1989, they began a college transfer program, offering associate’s degrees in arts and sciences, and allowing students and parents to use them as an affordable springboard to a four-year-degree. Again, there was opposition from USC, which worried that would steal its enrollment. There were still other concerns.

“There were a lot of people who feared that this would take us away from the technical in career education,” said Jim Morris, who was the executive director of the Technical College System from 1986 to 1994. “That has not been the case at all… We are all about job creation, but at the same time there are people who can’t afford the tuition at Carolina and other institutions of higher learning. They need an opportunity locally before they transfer… It was a wonderful thing, and I think the best thing that happened during my administration.”

Funding cuts devastated the technical colleges following the onset of the Recession. The schools offset some of the pain by raising tuition. Nick Odom, chair of the State Board for Technical and Comprehensive Education, which oversees the Technical College System, said in 2013, “We’re never going to see the level of funds from the General Assembly that we’ve seen for the last 15 years, and it’s diminishing, and may diminish more.”

And today?

The men and women who built the system are understandably proud of what they did. It stood out among all the states.

They had high hopes for future economic development driven by job training, and counted the presence of Boeing and BMW in South Carolina among their greatest hits.

However, on a list of 645 individual community colleges across the nation, measured by student-loan default rates, the absolute highest rate of default — the worst college — was South Carolina’s Denmark Technical College (motto: “Where Great Things Are Happening”).

In an overall ranking of 728 community colleges nationwide, considering cost and financing, educational outcomes, and career outcomes — from the cost of in-state tuition and fees, to student-faculty ratio, to graduation rates — with No. 1 being the best, Denmark came in at No. 724.

That list was selected from member institutions of the American Association of Community Colleges, by WalletHub, the financial services company, which has become adept at making such comparisons.

Piedmont Technical College, in Greenwood, came in at No. 704 on the list. (The college recently announced plans to construct a 47,000-square foot, $20 million Upstate Center for Manufacturing Excellence.)

Trident Technical College, in North Charleston, came in at No. 693. Orangeburg Calhoun Technical College came in at No. 689. Tricounty Technical College, in Pendleton, came in at No. 683.

Northeastern Technical College, in Cheraw, came in at No. 664. Florence-Darlington Technical College came in at No. 653. Greenville Technical College came in at No. 650.

Aiken Technical College came in at No. 648. Williamsburg Technical College came in at No. 620. Midlands Technical College came in at No. 590. And York Technical College came in at No. 574.

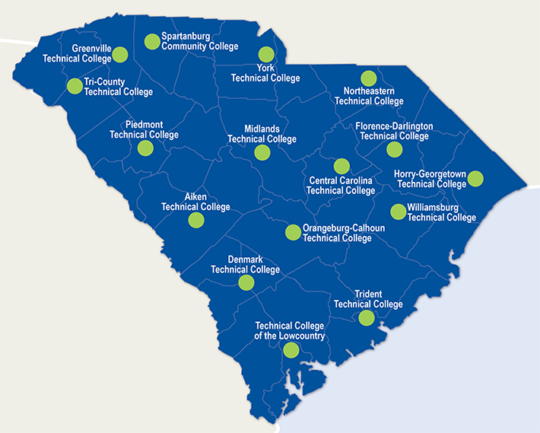

By this measure, 10 of the 16 colleges in the South Carolina Technical College System rank in the bottom 20 percent of all community colleges nationwide. The only other South Carolina community college on the list, Spartanburg Community College (it changed its name from Spartanburg Technical College in 2006), came in at No. 514.

On a similar ranking of states by community college systems, of the 44 for which there was sufficient data, with No.1 being the best, South Carolina comes in at … No. 43.

We asked WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez whether she thought it would be fair to conclude that by these measures, those schools are failing.

“It’s fair to conclude that these community colleges need to improve on offering good outcomes when it comes to education and careers,” Gonzalez said via email. “As things currently stand, these outcomes within the state are disproportional to the tuition costs and fees, as well as per-pupil spending.”

How alarming should this be to lawmakers and others who oversee the schools? we asked.

“Lawmakers should be concerned with the fact that South Carolina community colleges have fairly low graduation rates,” Gonzalez said, “ranging from 9 to 24 percent.”

Is this entirely a matter of funding, we asked, or are there other factors that contribute significantly to performance, such as leadership and policy?

“It is not entirely a matter of funding,” Gonzalez said, “since the average amount of grants or scholarship aids for some South Carolina community colleges are fairly high. It is more a matter of efficient spending.”

The other customer

We emailed President Ray Brooks of Piedmont Technical College, President Mary Thornley of Trident Technical College, President Walt Tobin of Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College, President Kyle Wagner of Northeastern Technical college, President Ben Dillard of Florence Darlington Technical College, President Keith Miller of Greenville Technical College, President Forest Mahan of Aiken Technical College, President Patty Lee of Williamsburg Technical College, President Ronald Rhames of Midlands Technical College, and President Greg Rutherford of York Technical College. Our questions were succinct: Providing links to the listings and methods, we asked, Why is this so, do you think, and what can be done to improve it?

None of the presidents responded.

Brooks forwarded the query to the Technical College System, which is the administrative head of the colleges, with its own staff, based in Columbia.

Kelly Steinhilper, SCTCS’s vice president of communications, said the analysis didn’t take into account the state’s lottery tuition assistance program, among other things, that “currently helps to offset tuition up to $1,140 per semester for our students. There are also several community-based scholarship programs designed to offset tuition costs as well as a pilot program funded by the state.”

WalletHub’s comparisons used data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics, which takes into consideration “aid received from the federal, state or local government, the institution, and other sources known by the institution.”

The state’s technical colleges educate and train nearly a quarter million South Carolinians, Steinhilper said in a prepared response to the study. “Ninety-six percent of our students are South Carolina residents and most of our students choose to live and work in South Carolina after completing their education. … 87 percent of our graduates are placed in a job related to their field of study or are continuing their studies and furthering their education. The system’s impact is far-reaching – much broader than reported in WalletHub’s study.”

Is there anything in the report of valid concern to SCTCS? we asked Steinhilper, and are there any areas here where SCTCS or the technical colleges are working to improve?

“Increasing completion rates across the System is always a focus for our colleges,” she responded, by email. “The more students we can graduate, the more skilled and ready people we can move into South Carolina’s workforce.”

And that may be one key to what’s going on here, in terms of rating the success of the state’s technical colleges.

They were set up to offer the best affordable educations to their students, but the primary objective was to train workers for businesses, especially for businesses that could be lured to South Carolina, rather than seeing job-seekers leave the state. So perhaps the schools’ value has to be measured in terms of what they’re worth to businesses as well.

For example, the new, $560 million Giti Tire plant, in Richburg, which is slated to start production this year, projects it will employ as many as 5,000 workers. Giti Chairman Enki Tan said recently that he is “passionate about working hand-in-hand with local school districts and technical colleges to recruit and train highly-skilled employees for demanding and highly-automated labor.”

Logically, or geographically, this would be in York Tech’s bailiwick. “Do you or your employees need professional development to learn new skills, or improve efficiency and performance in a specific area?” reads York’s website, under Workforce Development and Corporate Training. “Let York Technical College assess your needs and create training to meet your goals.”

When it comes to luring businesses — and jobs — to South Carolina, the technical colleges “are actually right at the table,” says Commerce Department Director of Marketing and Communications Adrienne Fairwell.

And that’s where Fritz Hollings hoped they’d be.

“They play a very large role in a company’s decision to locate to South Carolina, particularly because of the customized training that Ready SC is able to offer,” Fairwell continued. “They’ve played a very large role in training workers to be manufacturing-ready when Volvo comes online. It’s a vital component of what allows us to bring industry here, and to expand.”

So while value for students may fluctuate or decline, especially according to tuition and debt ratios, the other technical college customers, businesses, seem to still like free training just fine.